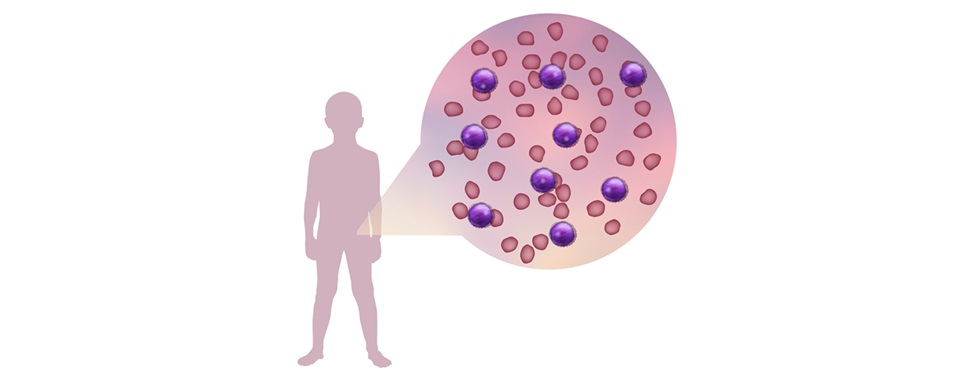

Ron Pettway was a happy, energetic toddler until the age of 16 months. That's when his legs stopped working. For months, doctors tried to figure out what was wrong. Eventually, they diagnosed Ron with myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder that affects voluntary muscles. Ron had a bone marrow transplant at age 13. He is now 22. Here his mother, Jessie Pettway, tells us his story.

What was your early experience with hospitals?

I found the care at other hospitals very frustrating. The doctors we met were very textbook oriented. That was fine when Ron was young because all the standard medications worked pretty well. But, as soon as he hit puberty, his biochemistry changed and the tried-and-true approaches stopped working. By the time he reached 13 he had almost no muscle control. He couldn't walk. He couldn't hold his head up. His breathing was very labored. His doctors kept saying, "We've done all we can do." At that point, I was sure we were going to lose him.

How were the doctors at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital San Francisco different?

For starters, the doctors at UCSF just looked at it differently. They constantly asked themselves: what else could we try? Other doctors seemed stuck in their ways, but the physicians at UCSF didn't write Ron off simply because he was not responding to the established protocol. They saw his case as a challenge, not a failure. And I can't say enough good things about Dr. Jonathan Strober. He just knew how to communicate with Ron. He saw him as a person, not a disease. When he came in the exam room, he could take one look at my son and know if he was having a good day or a bad day. It sounds so simple, but it made a huge difference. Ron felt like a doctor was finally seeing him as a person.

What about the nurses?

The nurses were amazing. When Ron first arrived at UCSF, he was black and blue from being poked with needles. He would tense up at the sight of a syringe, which would cause his veins to collapse. At other hospitals, the staff treated him like a pincushion. It sounds weird but at UCSF they were more loving. I'll never forget the first time the nurses came to draw blood. They asked Ron if he'd like them to numb the surface of his skin before they inserted the needle. We didn't even know that was possible. In all the years he'd gotten blood draws, no one had ever offered to numb his skin first. What's more is that the nurses at UCSF would look him in the eye and say, "Ron, if we can't get it in on the first poke, we'll just wait and do it tomorrow." They were not willing to traumatize my child if the test could wait.

How did Ron's treatment evolve?

Eventually, Dr. Strober told me he'd heard about another doctor successfully treating a patient with a disease similar to Ron's with a bone marrow transplant. I was thrilled. He asked us if we'd be willing to chart a completely unknown trail and we immediately agreed. I was so happy I wanted to cry. But first we had to figure out how we were going to pay for it. No one had ever used a bone marrow transplant to treat myasthenia gravis, so our health insurance company refused the request. Dr. Strober never gave up. He called. He wrote letters. I don't know how but somehow he convinced them to cover it.

What happened next?

We focused on finding a bone marrow donor. Because the best matches are often siblings, we tested Ron's three younger siblings. And, wouldn't you know it, his little sister Jasmine was a perfect match. Out of all of our kids, she is the strongest. She is healthy as an ox. We couldn't have asked for anything better. As a family, we took a collective deep breath and put our faith in God and the doctors.

Then what happened?

A bone marrow transplant is not easy. They first had to give Ron high-dose chemotherapy to destroy his old immune system. Then they pushed his sister's bone marrow through his IV. It was 5:07. I remember the exact time. It was the time of his rebirth. Afterward, he was isolated while his immune system took hold. The isolation was the hardest part. All four of my kids are very close. Ron has three younger sisters and they couldn't understand why they couldn't burst into his room after school and sit on his bed like they used to. To help ease the loneliness, the nurses bought walkie-talkies — one for Ron and one for his sisters. They also gave the kids duplicate board games. So even though there was a wall between them, our kids could talk and play games together. That's just one of the many ways that UCSF cared not only for our son, but also for our whole family.

On the day that he was discharged, the staff made a big banner. Everyone signed it. At the appointed time, everyone gathered in the hall, held up the banner, and cheered as Ron literally ran out of his isolation room. Four months earlier he'd entered the room in a wheelchair. He was too weak to walk. Seeing him run out is something I will never forget.

So the bone marrow transplant was a success?

Yes, knock wood. Ron got the bone marrow transplant when he was 13 and he hasn't been back to the hospital since. He's no longer on any medication for myasthenia gravis. His antibody levels are the lowest they have ever been. In hindsight, it was so simple. How could we have known that his cure was sitting next to him all those years?

What's Ron up to now?

Ron jogs every morning, lifts weights and does sit ups. He's going to college to learn animation. He's applying for jobs. He hangs out with his friends. He went from being in a wheelchair to playing basketball and graduating from high school. The most amazing day of my life was the day he walked across the stage to get his diploma. We still see Dr. Strober. We consider him a part of our family. If he hadn't pushed for the bone marrow transplant, I don't think Ron would be here today. Dr. Strober is my hero. He is the only doctor who said, "We need to try something different." He fought to save my son.